“A world that might have Bigfoot and the Loch Ness Monster is clearly superior to one that definitely does not.”---Chris Van Allsburg.

Prelude In A Rain Forest

Contrary to supposition by certain ethnic groups, the Hoh Rain Forest is located on the Olympic Peninsula in western Washington state and is a portion of the Pacific temperate rainforests ecoregion, the largest area of temperate zone rain forests in the world. To qualify for one’s Rainforest Pin, a forest must present evidence of a lot of annual precipitation and the Hoh does---about twelve to fourteen feet a year, much of it during the winter. Northwestern guide books will tell you it rains there every day of the year but Northwestern guidebooks would be wrong. It did not rain on Monday, July 10th, when Bill and Siobhan piloted their faithful Ford Flex the 87.8 miles from Port Angeles to the Hoh. Oh, it did glower and it certainly grumbled, suggesting showers were on the way. When that charade didn’t work and the forest gremlins realized our heroes were going to hike anyway, the clouds disintegrated, the sun came bouncing forth and the woods were illuminated in a bright neon green. Once again, perseverance wins the day.

The ecosystem of the Hoh Rainforest has remained unchanged for thousands of years and it is now the most carefully preserved rain forest in the western hemisphere, the only one with the distinction of being named a world Heritage Site and a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO. The most common types of trees growing there are Sitka Spruce and Western Hemlock, which can reach over 300 feet high and seven feet in diameter. Most of them are covered with huge clumps of hanging moss and ferns. There are also hundred-year-old cedars and firs. The trails are generally flat and easy to negotiate. One of the favorites, the short Hall of Mosses Trail gives the feeling of walking through a living green cathedral, especially on quiet days when hikers are minimal.

As we negotiated the well-maintained trails leading to the fast-flowing Hoh River, an unusual feeling of contentment came over me. I felt like I knew this place, recognized its colors, scents and sounds, was at home in its embrace. It was not a deja vu experience, more a feeling of having arrived in a setting which was specifically designed for me. For a brief moment in time, all concerns vanish, the subject is empowered, optimism reigns. The American Indians and other civilizations describe soul places, natural areas which speak to you in a language unheard by others, places a person can repair to for strength and renewal. Perhaps this was one of those. I kept telling Siobhan I felt very good here and asked her what she thought of the place. “It’s interesting and beautiful,” she replied, “and really unique.” The Hoh Rain Forest was all those adjectives and more. My own private Washington.

This is the forest primeval.

Surf City North

The road back from Hoh led through the boomtown of Forks, Washington, noted for being the rainiest town in the USA, but more famous for being the actual town where author Stephanie Meyer based her Twilight saga novels. We ate lunch in a small pizza place, empty probably due its prominent “VAMPIRES MAY NOT USE THE BATHROOMS!” sign on the door. Then we sped off to visit the Pacific Ocean, a mere 21 miles in the distance. Things were not exactly hoppin’ at windy Rialto Beach, a social gathering place for large pieces of driftwood, where it was necessary to climb over troublesome piles of rocks to get Rialto’s version of the sea. Nonetheless, one gritty family in topcoats sat around a table determined to enjoy a picnic, wind-chill factor in the forties or not. And it might as well have been Malibu to a quartet of five-year-olds frolicking at the water’s edge. As we keep reminding you, you can’t always get what you want but if you try sometimes, well, you might find you get what you need.

On the road home, we stopped to make the short hike to Sol Duc Falls, so named for the river which snakes across Highway 101 about seventy-five times. Since you’re wondering, Sol Duc derives from the Quileute word for “sparkling waters.” If you thought the Quileute tribe had become extinct, nope, there are still a few of them down the road at La Push, drinking Chuckanuck beers and running their marina. If you decide to drop in, they don’t like Tonto jokes.

The Sol Duc Trail is a moderate 1.7 miles out and back through an old-growth forest culminating with a rollicking waterfall, passing over a few spring-fed snow runoff creeks along the way. A good way to wrap up the Washington hiking and contemplate the next day’s drive to Mt. Saint Helens. On the way back to Port Angeles, we called Judy at Kokopelli’s to make reservations at the city’s best restaurant. We had a sparkling conversation, the kind you want to have with people who can easily dump you in a restaurant’s cellar. When we got there and meandered through the waiting crowds, Judy’s accomplice led us upstairs to the best table in the place, one with a grand view of the water and the arriving boats. A fitting final gift from the town, a proper sendoff from dependable Port Angeles.

Ravishing Rialto Beach. Views from the Sol Duc Trail. Last meal at Kokopelli’s.

Ashes To Ashes

Nutritionists are always telling us that breakfast is the most important meal of the day. On May 18, 1980, it was the most important meal of Trixie Anders’ life. While her friend and fellow Washington State University geology student, Jim Fitzgerald, had gone on ahead to get a close look at the grumbling Mount Saint Helens volcano, Trixie stewed at the Highway 504 cutoff near Toutle while her husband finished his eggs. Fitzgerald snapped 14 frames before the eruption blew him to kingdom come, the pyroclastic surge sweeping over him at 500 mph. His film survived but Jim was….well….toast.

The Anders Jeep went screeching down the hills with reckless abandon. “We’re driving so fast I was sure we’d flip it,” said Trixie. “We were going around corners on two tires. I’m hanging out the back taking pictures thinking either the mud or the surge was going to get us. It’s almost like your brain can’t realize what’s happening because you can’t hear anything. It looked like an atomic bomb going off, a silent atomic bomb. I thought we were dead but the surge hit a ridge and went shooting into the sky.”

Meanwhile, Mike Moore of nearby Longview picked out a spot on the Green River about 13 miles northwest of the volcano to watch the action. He brought along his wife, Lu, and daughters Bonnie, 4, and Terra, 3 months. “We didn’t hear an explosion,” related Mike, “just a loud rumbling, like an aircraft way up high and in trouble. Right after that, the air began to compress around our bodies, squeezing us like you were coming off a high pass at 1000 miles an hour.”

Moore grabbed his camera and started taking pictures. The cloud from the volcano continued to grow until it filled his viewfinder. He looked skyward and saw roiling black clouds of ash racing overhead, then yelled at his wife to get everybody into a nearby hunter’s shack. They made it just as the ash cloud enveloped the area, blowing down trees and sparking a lightning storm. “Light dropped to zero,” Moore said. “You couldn’t tell if your eyes were opened or closed.” He and his wife wrapped the baby in blankets to keep the ash out of her lungs. “The rest of us got out our extra socks, got them wet and breathed through them.”

When the cloud passed, the family emerged into a black and white world six inches deep in ash. They put the baby into Moore’s backpack and spent most of the day trying to make it the two miles back to their car, constantly foiled by uprooted trees in their path. They spent the night in the woods and were rescued by helicopter the next day.

National Guard pilot Jess Hagerman spent the day flying the Toutle and Green river valleys, looking for survivors. “The sky, the ground, everything was basically the same color, it was all one shade of gray,” Hagerman reports. At one point, about 14 miles from St. Helens, Hagerman spotted tracks in the ash. He followed them until he found two men on a road along the Toutle River. The two were part of a logging crew caught in the surge. One man was on his feet and asking for pain medication. “He’s 14 miles from the mountain and he has these big welts on his face,” Hagerman said. “His hands are black. I later learned that was because his gloves had fused to his hands.” The pilot flew the men into town. The man with the welts survived, his partner didn’t.

Nor did 56 others, most of them from asphyxiation after inhaling hot ash. The names of the dead are prominent on a wall at the Johnston Ridge Observatory, the closest spot to the mountain paved roads can take you. Inside, two alternating movies of the catastrophe are shown every half hour detailing the buildup to the eruption and the surprising ecological comeback the area has experienced in the 37 years since.

The mainland of the United States has nothing to compare with the incredible scenario offered by Mt. St. Helens. The mountain is over 50 miles from the main highway through the area, however, approached only via narrow, winding roads which take time to navigate, thus there is a visitor center at the end of an exit ramp for skimmers who like to buy postcards and check prominent sights off their “places visited” lists. If you’re in the area, don’t you be one of them.

Mt. St. Helens---the blowout area.

Siobhan tries to focus. So does the camera. Siobhan does better.

The curtain rises at the end of the movie to reveal….

Going Ape

Yo-ho, yo ho, it’s off to the cavern bottom we go,

We’ll bring some bananas and a gift box of lichees

To let the apes know we’re friends of the species.

Bigfoot or Sasquatch or the Abominable Snowman, all are big business in Washington state. The retailers sell renderings of the big feller on tee shirts, hats, cocktail glasses and mud flaps for your truck. You can buy a Sasquatch Sandwich (curiously invented in Minnesota) or a Bigfoot Tree Knocker or even an Abominable Lunchbox for your kid. All this and nobody’s seen a Sasquatch in years. The locals still delight in warning rube tourists to avoid certain trails because “people have been disappearing from that area lately.” Try talking your wife into trekking down one of those paths. Not that anybody really believes in the things. It’s just that, well, you can’t be too careful these days, right? We went to the Ape Caves anyway.

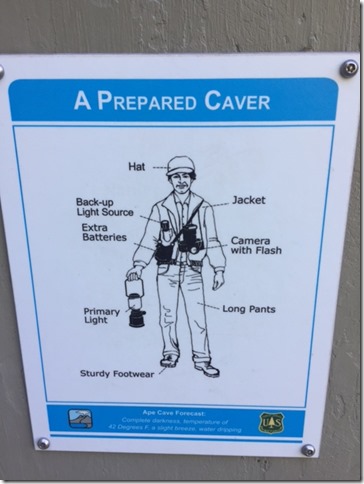

The Ape Caves are lava tubes on the south side of Mt. St. Helens, (the opposite side from the Big Blowout), about two miles in length. That makes them the longest lava tubes in the continental United States and without much competition, I’m guessing. It is very, very dark in the Ape Caves. Hikers are advised to wear a helmet with a light, wear tough shoes that can handle the rocky, uneven surface, use gloves in case they happen to touch the damp, oozing wall and carry a flashlight in case the headlight goes out. Since quarters can get tight, backpacks are verboten. Cavers are advised to turn around and go back if the going gets too uncomfortable. I mean, you wouldn’t want to get stuck in there, would you?

Siobhan and I arrived at eight o’clock in the morning, preceding everyone else. Even the rangers don’t show up until nine. If we ran into trouble at this hour, too bad. Naturally, we were ill-prepared with no headlights or gloves, equipped only with a pair of five-dollar flashlights purchased the night before at Safeway. Well, what are the odds they’ll both go out? That wily Siobhan brought an extra battery just in case.

There are, in fact, two Ape Caves, a higher and more difficult tunnel with more rocks and worse footing and a lower cave with fewer deficits. Being rookie cave explorers, we chose the path most traveled. We descended a ladder of several steps and entered the pitch-black cave, happy to see that our flashlights seemed adequate. The ceiling was high and the rocky floor varied between even patches and toe-stubbing blockades. We stumbled along for quite a while expecting to reach the exit soon, when what to our wondering eyes should appear but a slowly narrowing ceiling. Feeling it was just a temporary inconvenience, we moseyed on, stooping down a little bit to avoid the drippy roof. Uh oh. The ceiling kept getting lower, lower, lower. Never one to adhere to silly rules, I was carrying a small, thin backpack, but even that was rubbing against the top of the cavern. Siobhan, being smaller, decided to go ahead. She crawled on her hands and knees for some time, then reached a small wall. “I think if I get over this,” she reported back, “I can stand up again.” She got over it. She stood up. She circled her flashlight around. Uh oh, again. “There’s no way out,” she advised. The cave just ends.”

We had paid too little attention to the details of the map, which celebrated a nice little hike at the end of the tunnel. That would be, of course, the upper cave, which we were not in. Since we were carrying no blasting materials, we crawled around and turned back, retracing our steps to the entrance. People were beginning to arrive as we departed, many of them as confused as we were. We performed our due diligence and straightened everyone out, then took a short hike down a nearby trail and moved on. Despite our mistake, we were glad for the visit, the experience, the stories we could tell. Returning to the parking lot, I nonetheless addressed Siobhan in grave tones. “Batman never has days like this,” I complained.

Prepared caver.

Fun-boy caver.

Into the maw.

Hallooo! Anybody home in there?

On the Lava Canyon Trail. Bridges over troubled waters.

That’s all, folks….

Note: Sometimes, much to the chagrin of our old pal Chuck Lemasters and perhaps others, the photographs herein are not perfect. Noone knows this better than us. Sometimes we’re in a big hurry. Sometimes the lighting is terrible. Sometimes it’s foggy or hazy or misty or dark. Sometimes we screw up. But we decided you’d like to see the places we visited, anyway, perfect or not. Maybe some day we’ll go to photography school. Probably not. We’d take Chuck along but you know how he is about guarding his vast agricultural interests.