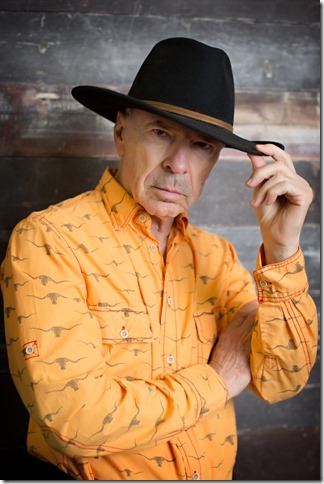

The old Oklahoma State Cowpoke at 76. Giddyap!

“He who follows the crowd usually gets lost in it.”---Anonymous

“Growing old is mandatory; growing up is optional.”---Chili Davis

If Meredith Wilson hadn’t decided to have 76 trombones lead the big parade, the number would long ago have been surrendered to antiquity, buried in deep cement along with “the Spirit of “76” and the perennial last-place Philadelphia 76ers. After all the foofaraw assigned to 75, with its Golden Jubilees and Diamond Anniversaries, 76 is anticlimactic, more so in the face of the onrushing 77, the doubly lucky year of payoff promises on champagne wishes and caviar dreams. Seventy-six is a mere waiting-room at an uncelebrated outpost, an overlooked interstate exit devoid of a McDonald’s, a twelve-month vacation in Lubbock. Or so the unschooled observer might opine. If you happen to be a member of the exclusive 76 ‘R’ Us Club, well, it’s an entirely different matter. Seventy-six becomes another 365 days to celebrate life, a year to further explore this incredible planet, one more opportunity to undertake tasks undone and reconsider hopes unmet. If life is not a bowl of cherries, it is at the very least a bowl of opportunities sitting there for your own purview. What’ll it be this year, feast or famine, repose or revival, celebration or regret? As usual, it’s up to you. The years are marching and the pace is swift but the pinata is still hanging in the tree. Don’t be afraid to grab a bat and bust it open. I promise you’ll be glad you did.

Battling The Plague Of OPE

When we were kids, we were ripe for the plucking by the minions of the Roman Catholic Church, who saw in us not a gaggle of little ballplayers, cowboys and Indians but a ripe reservoir of talent, sustenance for their gigantic maw, more fuel for the Vatican’s fire.

In the third grade, Sister Mary Albert, a formidable and crotchety old nun, took time from teaching long-division to ask how many of us would be joining the choir. Every single kid in the class raised his hand, as expected. Well. Every kid but me. This was a shocking happenstance for Sister Mary Albert, almost a personal rejection of herself and all that was holy, because choir participation was step one to becoming an altar boy, several of whom were then pushed and prodded at a too-early age to consider whether they had a “vocation”—a calling by God to the priesthood. The nun felt it was a personal challenge to change my mind.

“William Killeen—why are you the ONLY boy in this class who does not want to join the choir?”

“I’d rather go home and play baseball, Sister”

“And who will you play with if everyone else is at choir practice,” she asked, smugly.

“Protestant kids.”

You could have heard a pin drop. PROTESTANT kids? Who knows what that could lead to? Why, some Protestant kids didn’t even go to church on Sunday. There was an uncomfortable giggle among the students, quelled with the triple rap of Sister Mary Albert’s pointer on a nearby desk. “We’ll talk about this later, Mr. Killeen,” she said. “Mr.” was always what the nuns called a kid when they were pissed off at him.

The sister sent a note to my parents. My mother pushed me to comply but my father, no big fan of the nuns, overruled. “You can do what you want,” he said. “The nuns don’t run the world.” So thanks to Thomas Joseph Killeen, I was spared a descent down the Catholic rabbithole, a one-way street to boredom and misery. One day, I was the rebellious center of scorn and derision, the next day the hero of the class, the leader of the Resistance, someone the other kids could cite to their parents as an example: “Well, Billy Killeen doesn’t have to go!” God knows how many little lives I saved.

It’s never over until it’s over, of course. For the rest of the elementary grades and even into high school, the campaign for vocations might have rested but never ceased. Quiet loners, kids who had trouble fitting in or were unpopular for whatever reasons children devise, were especially vulnerable. The Church scored its share of victories. Some kids, even some parents yielded to Other People’s Expectations. But at least they gave up on me. They never bothered Billy Killeen again. It was not so much a principled stand but more a willingness to fight for my time and to spend it how I wished despite pressure, regardless of disapproval, frowns and scolding. When this works once, you have a tendency to keep on doing it forever. Even for 76 years.

There’s Nothing So Plentiful As Advice

When I was in high school, it seemed like every second adult I met had advice for me, much of it about what path to take to riches. “Billy, get into engineering,” I heard more than once. “That’s where the money is.” It seemed of no consequence to anyone whether or not a person actually liked the notion of being an Engineer, the job promised a secure living and you could learn to like it. You had to remember that most of these advisors battled gamely through the Great Depression where jobs were scarce, millions were broke and security was a foremost concern. Having none of their psychological deficits, you would have had to hit me on the head with a large hammer to have me consider Engineering school. Since the Red Sox had not had the good sense to sign me to a baseball contract, I was heading in the direction of Journalism, where the pay was less but the non-remunerative rewards were greater. At Oklahoma State University, I wrote a ton for the student newspaper and eventually started up my own off-campus college humor magazine, the State Charlatan, against the advice of….well, everyone. Other People expected me to fail.

Bill, what do you know about putting together a magazine, they’d ask. Well….nothing. But, like anything else, it’s a series of steps, right? First, you write the copy, then you draw the pictures and take the photographs. After that, you decide where everything goes. Then you find a printer. Common sense. Turns out it’s a bit more complicated than that what with advertisers to hunt down and satisfy, staff members to hustle and decisions to be made on how and where to sell the thing, but nothing requiring a degree of genius. You make mistakes. You learn from them. I figured all this out after my first high-school typing class. On day one I went in there, sat down, looked at the typewriter and thought there is no way in hell I’m ever going to learn this. But I did, of course. A series of steps. Works every time. Worked with the Charlatan, a product which sustained me and gave me purpose during adolescence and beyond. And all because I didn’t back off in the face of sarcasm or question my ability to do it. Didn’t yield to Other People’s Expectations.

Halfway through my third year of college, I moved to New York City to learn the magazine business from a man who published a fleet of the things. Discovered the virtual impossibility of succeeding with a home-made operation just from the dynamics of distribution. Newsstands were much smaller then and every space on the seller’s rack was coveted and generously paid for. When I returned to Massachusetts for a few months, my mother constantly shunted me towards a job at Raytheon or Western Electric, both good-paying outfits. “They have a lot of fringe benefits,” she reported. “And there’s room for advancement.”

“You sound like a commercial, Ma. I’m sticking with the magazines.” My mother, having seen me drop out of college, feared I might fall by the wayside and wind up living under a bridge. Instead, I moved to Champagne-Urbana and worked for a magazine called Chaff for awhile, then emigrated to Austin and helped with the University of Texas humor magazine, the Ranger. It was 1962 and nearing the end of the beatnik era. All of our parents had the same fears: their children were circling the drain, dressing funny and engaged in wild pursuits. God only knew what would happen next.

I took the Charlatan to Florida, first to Tallahassee, then to Gainesville, and made enough money to get by. In 1967, I had accumulated all of $1200. In the summer months of the late sixties, the University of Florida virtually closed down so there was no magazine income for that third of the year. I thought I might open a bookstore….sell underground newspapers, marijuana growing guides, posters and comics .There were tons of new products popping up daily, enough to get me through til Fall. Other People laughed, of course. What do you know about opening a store, Bill? Well, uh….

Two people who didn’t laugh were my girlfriend, Pamme Brewer and one of my housemates, Dick North, who saw the new shop as a potential host for his leatherworking enterprise. “So what if you never ran a store,” Dick said. “Most of the other people who opened stores never did it before either. They were just older, that’s all.” Finally. An ally against Other People’s Expectations. We opened the Subterranean Circus in late September of 1967 and it took off like a rocket. The transformation of Hogtown had begun. Before long, Gainesville was full of little stores operated by people in their twenties. Ira Vernon started selling jeans and tops at Tuesday Morning, a couple of blocks from campus on University Avenue. Doug Bonebrake opened Mother Earth on 13th Street, just south of the 8th Avenue overpass. Dudley Whitman went into the hamburger business at Snuffy’s, a few blocks from the Circus. All of these and several other small businesses rose and persevered for years at the height of and in the waning years of hippiedom. It was a most unlikely time, an era of creativity and magic, and nobody thought anything impossible. The most unlikely operations appeared from nowhere, generated their powers and flourished. Music filled the air, along with the obvious scents of sandalwood, patchouli and marijuana. In Camelot, that’s how conditions were. And nobody, make that nobody, paid too much attention to Other People’s Expectations.

A Brief Conversation With Janis Joplin

If anyone could be considered the Patron Saint of not acceding to Other Peoples’ Expectations, it might be Janis Joplin. She did it her way, sometimes adroitly, occasionally clumsily, and devil take the hindmost. For Janis, the world was divided up into two factions, the hip people—she, her friends and anyone she admired—and “the straight people,” which was everybody else. She realized it was occasionally necessary to interact and cooperate with the straight people but she wasn’t cutting them any slack and she certainly wasn’t taking any guff.

I met Janis in 1962 when I was 21 and she was 18 at an early-evening party at the off-campus apartment of Neil Unterseher on Guadalupe Street near the University of Texas. She came to the affair in her usual uniform—black turtleneck, black jeans and little black boots—carrying an equally black autoharp. It was a common occurrence at Austin parties for some of the guests to dance, to make music, to sing. But not like this. Not like the new girl in the black sweater, pants and shoes. Not like Janis Joplin.

It was folksinging in those days, and old Protestant church songs and The St. James Infirmary Blues. But whatever it was, it was special in Janis’ hands. Not many music-makers thought in terms of becoming famous in those days. The question then was, “will we make it,” will we survive and be successful in this life and, if so, how much of our natural selves will we have to forfeit? For Janis, the answer was: none. None is a tough row to hoe but Janis was a diligent gardener.

Janis was exceptionally intelligent, very artistic and extremely funny. Tell any joke, she got it immediately. She could siphon humor out of a disaster and was very quick to laugh at herself. Once, after having cooked an inept meal, she threw the plates in the sink and wailed, “I’m a domestic failure, a complete disaster!” but the way she did it made it seem like you were reading her comments in a word-balloon from a cartoon, which is what she intended.

I left Neil’s party with Janis and Lieuen Adkins, a member of the Texas Ranger humor magazine staff, like myself. We wandered past the State Capitol building and down Congress Avenue to get something to eat at a small restaurant and watch the counter crew chase a bat around. Eventually, Lieuen, who lived at home and had a curfew, disappeared and Janis and I emigrated to the foliage around the Capitol, where we spent the night, impolitely roused in the early morning by a security guard. A few days later, I went to Houston in a vain search for an editor’s job with Trans-Texas Airways. By the time I returned, Janis had abandoned her apartment and was living rent-free in a house near UT just off Guadalupe. The place was owned by the father of her friend, Win Pratt, who was blissfully touring Europe with no idea his son was off donating his real estate. We lived there together for a couple of months until the elder Pratt returned and routed all the squatters. During that time, we had endless conversations about life and love and music. And about what Janis called “selling out,” which sometimes meant meeting Other Peoples’ Expectations. Those discussions, carried on over many weeks, are compressed here for brevity’s sake.

JJ—Killeen, you’re a writer—I need some writing tips. What if I want to write some of my own songs and I can’t figure out how to get started?

BK—Well, DO you want to write your own songs?

JJ---Maybe. Bob Dylan writes his own songs.

BK—Yeah, but a lot of people don’t. Joan Baez doesn’t write her own songs. Elvis didn’t. Hell, what about Frank Sinatra—he didn’t write a thing. What do you want to write about, anyway?

JJ—I dunnow. Teen angst (laughing). Sordid romances. The heartbreak of psoriasis (laughing hysterically).

BK—Maybe you should do it. You know a lot about teen angst.

JJ—I do, but I’ll be twenty in less than two years and it may become just a fond memory. I think I should write while I’m immersed in pain and confusion.

BK—What’s going to happen when you’re twenty? Are you trading in your black outfits for pink?

JJ—Are you assailing my WARDROBE? (titter)

BK—I wouldn’t dare.

JJ---My mother used to tell me, Janis, you’d do much better with the other kids if you didn’t dress so weird. She pounded on me about it all the time.

BK---Your mother foresaw the likelihood of teen angst.

JJ---Well, I’m not gonna let the straight people beat me down. I’ll wear what I damn well please. You like me anyway, don’t you Killeen?

BK---Sure, but I’m not known for my discriminating tendencies. (pillow flies across the room)

JJ---Somewhere along the line, you’ve gotta decide whether you’re gonna be yourself or sell out and do what everybody else thinks you should do. Even if you get hassled by dumbass fraternity boys all the time. Hey—one of them called me ‘that beatnik chick’ the other day. I think he inferred that I was unkempt.

BK---Well, I guess you’re just lucky some of us like unkempt beatnik chicks.

JJ—Outcasts have to have their heroes, too. Maybe I’ll make it as Queen of the Outcasts. When I do, I’ll get a big Harley-Davidson motorcycle and buy all my followers greasy leather jackets. We can all be unkempt together.

I saw Janis one final time after she became famous. I climbed a high hurricane fence at the first Atlanta Pop Festival, dodged security and ran into the Queen of the Outcasts walking to her trailer. She actually picked me up, swung me around and advised me that she was now “ a fucking corporation,” laughing her head off at the wonder of it all. We discussed old times, commiserated over friends lost to the ethers and soon it was time to go. Janis jogged off a few steps, turned around and hollered, “Hey Killeen—I know you’re proud of me. See—I made it and I didn’t sell out!” And then she ran off into the cacophany that only angst-ridden beatnik chick megastars know, while the rest of us stand in wonder.

Etc.

That’s almost all, folks. Except for Photographic Credits to Jaime Swanson, who is rapidly becoming the Flying Pie House Photographer. Jaime shot last year’s “Bill Is 75” pictures and did such a fine job we brought her back for an encore. Besides, you know how hard it is breaking in a rookie where nude old gaffer shots are concerned.

Jaime runs a Gainesville operation called Sweet Serendipity, which might be an okay name for a babies and brides photog but hardly seems appropriate for this sort of work. Maybe a side studio called something like “Bare With Me” or “Naked Ambition” would be good.

Last year, one of our readers told us he was having trouble coping with these annual birthday suit pix and we can understand. We’ve found, however, that if you know you will be appearing naked in public every November 2nd, it keeps you from letting yourself go. It’s a philosophy which has worked well for many years for the other Naked Cowboy, the one in Times Square, who is also—to quote Janis—“a f**king corporation.” Now if I could just learn to play the guitar….