You never forget your first, or so they say. My first thoroughbred foal, eventually named Star Spectre, was born on April 26, 1976 at the Sleepy Hollow horse farm in Micanopy, about a half-hour’s drive from Gainesville. His mother, Bonquill, was boarded there while wife Harolyn and I awaited completion of our own farm in Orange Lake. Night after night, we made the trek, often with a coterie of friends, sitting up with the mare long into the night, movie cameras at the ready in avid anticipation of the blessed event.

When Star Spectre was finally born, we fussed over him as much as one would a human infant, visiting constantly, playing with the little critter, taking hundreds of pictures, even holding his bowl under his nose until he finished eating. Star Spectre developed into a muscular colt, a good-sized chestnut, very attractive, with chrome halfway up all four legs. He broke his maiden at a flat mile in his third start at Arlington Park outside Chicago and was nominated for the 1 1/8-mile Florida Derby, his pedigree suggesting the longer a race was, the better. And then, of course, he broke down, bowed a tendon, which is like a shot between the eyes to a racehorse. We gave him away to a crusty old trainer who brought him back to the track a couple of years later and won a few cheap races before the tendon acted up again. By then, we had half-a-dozen mares and the foals were coming left and right. Each birth was still exciting, most of them easy, a few precarious, although they could never equal the drama of the first foal.

Time went by, things changed. Harolyn departed from the scene, taking a couple of mares with her. My own herd of mares increased to fifteen, which is a lot on a 40-acre farm. The birthing season stretched from January until June, now more of an everyday business challenge than a source of celebration. Sure, it was fun to have the newcomers around, but there were mares to be teased, booked and bred, ultrasounds to be performed, medications to be administered, veterinarians to be consulted. And then there were the stallions.

The old adage encouraging the breeding of the best stallion to the best mare is naive and shortsighted. Even assuming you can afford to breed to the best stallions, there’s a little matter of pedigree to consider. What’s your objective? If you’re trying to win the Kentucky Derby, it might be a good idea to abstain from breeding to a sprint champion. If you want your eventual two-year-old to work in 9.75 seconds for a sale, keep that sprint champion in mind. Some breeders attempt to compensate for shortcomings in their mares by breeding to stallions which don’t lack the same qualities, which is fine as far as it goes. But body types matter. Breeding a tiny mare to a giant stallion is not usually a good idea. On the other hand, breeding a bad-legged mare to a very correct stallion makes a lot of sense. If you’re all in a quandary, they have experts for these things, although I’m not sure they do any better than the rest of us. On the whole, it’s a lot of work.

Every day you’ve got almost undecipherable problems. If a stallion is popular, everybody will be breeding to him, perhaps even you. The vet checks your mare and advises that Thursday morning will be the optimum breeding time. You call the stallion facility and discover that slot is not available. You can take an evening breeding, the stud’s third of the day, or opt for the next morning, when he is fresh and perhaps more fertile. Or maybe Wednesday night. Is that too early? Is Thursday night too late? How long is this particular stallion’s sperm viable? What does the vet think? Does your chewin’ gum lose its flavor on the bedpost overnight? There are no answers, only mysteries. You do the best you can.

More time goes by. If you’ve made good decisions and all your mares get in foal, you look up one day and you’ve got fifty horses on your forty-acre farm. This is not necessarily a good thing. This means you’ve got to feed fifty horses, get the blacksmith out for fifty horses and eventually train all those slated for the racetrack. Old horsemen like to tell one another about how to make a million dollars in the horse business. “Start with TWO million,” is the advice. And they’re not kidding.

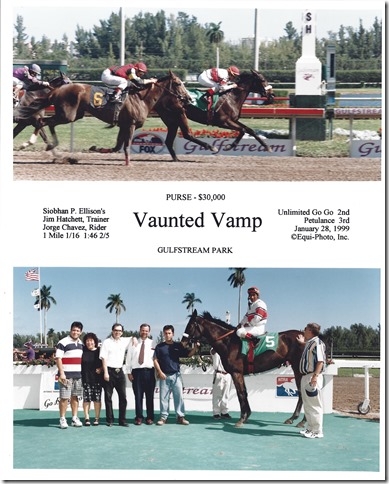

If all this sounds like so much complaining, it isn’t meant to be. There is adversity in all enterprises and at least ours isn’t boring. Where else can a guy with a head shop on the corner wake up one morning, get a phone call and find out he’s just sold an item for half-a-million dollars? That’s a lot of sassafrass incense. Or, in a year when he has just a couple of foals, wind up with one who wins a pair of $100,000 stakes races and goes on to compete against the best three-year-olds in the country at Keeneland? Where else, for crying out loud, can a guy get a Vaunted Vamp?

Vaunted Vamp

Every so often, one of those crazy fools who waits in a mile-long line to buy a $50 million lottery ticket actually wins the lottery. His chances, of course, are only slightly worse than those of a thoroughbred breeder having a great deal of success with a donated mare bred to a free stallion. But every once in a while, when the planets are correctly arrayed, the Cosmic Arbiter decides to display his wry sense of humor by plunking down a marvelous racehorse in the middle of nowhere. So it was with Vaunted Vamp.

One of the local horse farm owners decided he’d had enough of the business. He offered his veterinarian, Siobhan Ellison, a mare named Peace and Quiet, undistinguished but attractive, which Siobhan intended to use for a riding horse. Alas, Peace and Quiet did not live up to her name, displaying neither peacefulness nor quiet and disqualifying herself from riding-horsedom. Before dumping P&Q, Siobhan offered the mare to me. I looked at her pedigree, unimpressive but interesting, and took her. I bred her to a first-year stallion standing at Farnsworth Farm named Racing Star, a multiple stakes-winner known principally for his grass prowess. In speed-crazy Ocala, a grass horse was unlikely to set the stallion world on fire so Farnsworth offered his services for free. If the stud was successful, they could worry about charging stud fees later. The breeders proved right however, as Racing Star sired little of consequence. Except in the singular case of Vaunted Vamp, who wound up winning 21 races and over $420,000. During one of our delightful trips to the Calder Race Course winner’s circle, an amazed owner with horses in the same barn told me, “I hope you realize you will never have another horse like this. Even great horses don’t win this many races.” Maybe he jinxed me, but he was right. Episodes like this one, however, are the cream on the enchilada, the horseman’s raison d’etre. They atone in part for all the aborted fetuses, crooked foals, racetrack failures and other disappointments horse owners contend with daily. Nonetheless, the weight of those encumbrances over time takes its toll. And as we age, our tolerance for disappointments withers. After all, the list of negatives that oldsters deal with is long and challenging already. Nobody is looking for another lousy phone call.

The Evil Dissipation Blues

I can’t put my finger on when it starts or why, but one curious day most of us begin sliding into a strange mental ravine. We begin staying home more. We’re less likely to attend events after dark. Long trips other than the annual vacation become rare. What the hell is going on? Oh, I realize that health issues play a part. Diminishing vision discourages night driving. Venues which require lengthy perambulation from the parking lot are hard on old knees. Party time is much less festive when some of us are no longer allowed to drink. But a lot of people who are in exemplary shape contract the same disease. Even me.

After a couple of decades of travelling to Knoxville in alternate years for the Florida-Tennessee football game, one year Siobhan and I decided it was just too much of a bother. And that was with the benefit of her brother residing in Chattanooga, where we spent the nights before and after the games. It wasn’t the football. Florida, which has beaten the Vols eleven straight years now, almost always won and the games were close and well-played. We enjoyed visiting the relatives, who provided a fun environment and comfortable amenities. Why then? Who knows?

I used to go to all the University of Florida home basketball games, generally buying my tickets outside just before tipoff. I haven’t had many wives or girlfriends who were big sports fans so I went myself. One year, I met a fellow named Torrey Johnson there and we bought adjacent seats. After that, we met outside the arena before the games and continued to sit together. Basketball was more fun with Torrey but eventually he moved to South Florida and I continued to go on my own. Then one year, I decided I’d had enough of pre-season exhibition games against inferior opponents—usually won by the home team by scores like 200-12—and I didn’t go. If I wanted to watch, they were on television, after all. After awhile, I started skipping other contests I perceived to be less than competitive but continued going to the conference games. But that ravine has a slippery slope. Once you’ve got one toe in the mud, you start sliding further down. Last year, I went to UF games exactly twice, watching the rest on TV.

For years, Siobhan and I went to the movies every Friday night. People with gleaming cell phones—instruments which flashed like so many dancing fireflies—drove us away. Are we just old and crotchety? Do we get pissed off too easily? Are we turning into (shudder) Republicans? Maybe it’s just an unexplainable factor of age. Maybe we have an intangible monitor which starts reining us in when we reach a certain number, the same one that tells us we can’t wear mini-skirts and Metallica t-shirts any more. So thank God for those among us like Mick Jagger who manage to turn the damn thing off for awhile. Remember, Dylan Thomas gave us clear instructions: “Rage, rage against the dying of the light!” Is anyone still paying attention?

The Last Foal

As you get older, the chore of foaling mares and raising babies seems to get tougher. The physical aspect—staying up for endless nights watching mares, wearily cleaning and rebedding stalls the next day, sacrificing time which could be spent on other activities—is one thing. The psychological aspect is another. Sometimes, things go dreadfully wrong. Our penultimate foal, a healthy colt at birth, began weakening by the day with a heinous condition called neonatal isoerythrolysis, which occurs when a foal is born with a blood group that is different from its dam and then receives antibodies against those red blood cells through the mare’s colostrum, leading to the lysis of the baby’s red blood cells. By the time anyone notices what’s going on, it’s almost always too late. We transfused the colt at a healthy cost of $1000 but he continued to fade and died shortly thereafter. When he could no longer rise on his own, we took him out of his stall into the sunshine on a sled and back again in the late afternoon. Talk about your long day’s journey into night. This was the last straw for Siobhan. We agreed to curtail the breeding operation and find future racehorses at yearling or two-year-old sales. Winning a big race with a homebred you foaled and raised is more gratifying, of course. But all of those beaming owners with purchased horses on their way to the winners circle don’t seem to mind.

So now there’s April, The Last Foal, a filly by Uncaptured out of Cosmic Light, a bright little creature, strong, quick to get up and get running. When approached, April is tolerant, unfrightened, a confident look in her eye. Her legs are straight and her size is good. She traces back to my second racehorse, Deadly Nightshade, less than a champion but never a quitter, always advancing at the end of the battle. If you always remember your first foal, let’s hope we always remember our last, not for her chronological order but for her talent, her gumption, her quality, her achievements. It’s all up to you now, April, so grow in strength, deepen in character, broaden in courage and gain in speed. And maybe, just maybe, we’ll remember The Last Foal most of all.

That’s all (for now) folks….