When we were kids, Saint Patrick was a ubiquitous presence before we even knew what the word meant. We attended St. Patrick’s Parochial School, went to mass at St. Patrick’s Catholic Church and lived in St. Patrick’s Parish. If we wanted to play basketball, it would be for the St. Patrick’s Shamrocks, Celtics, Gaels, Irish or Harps. It was all St. Patrick, all the time, even if you were Polish, like Joey Posluszny.

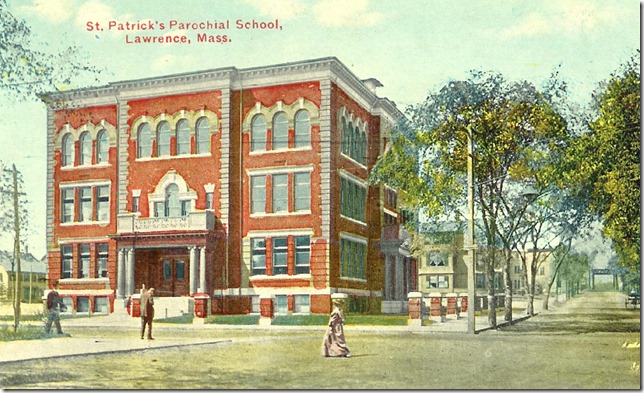

St. Patrick’s school was originally one three-story red brick building on the corner of Parker and Salem streets in Lawrence, Massachusetts, built in 1906. More buildings, including one for a girls’ high school, were added as the place thrived. St. Pat’s was operated by the no-nonsense Sisters of Charity, who lived directly across Parker Street in a very nice—and large—convent. The church was a few blocks west on Salem Street. When you eventually got married, it would be at St. Patrick’s Church and when it came time to haul you away, that’s where the parade would start. To say we were immersed in St. Patrick would be an understatement, but that was okay. We loved the guy. After all, as they say in the hymn, “There is not a Saint in the bright courts of heaven more faithful than he to the land of his choice.”

We arrived at school by eight o’clock in the morning and left there at three-thirty in the afternoon, with a short break for lunch, spent by some at Al Thompson’s variety store just across the street, which sold everything you needed and plenty of stuff you didn’t. When it was time for class, we dutifully lined up two-by-two in the vast, fenced-in schoolyard and waited for the public address system to blast out Stars & Stripes Forever or some such fervid ditty and promptly marched—that’s right, marched—into class. The Sisters of Charity were nothing if not anal about order.

Not to mention about the Separation of the Sexes. The schoolyard featured a long white painted line—about a foot wide for emphasis—which separated the boys and the girls. Woe betide anyone caught malingering on the wrong side of that line. If you wanted to hustle Dodo Miskell or her older sister, Judy, better do it before you entered the gates. And don’t even think about reaching across that line to touch somebody. Better to have a coal mine fall in on you than incur the wrath of the nuns.

The Sisters of Charity were well equipped for their tasks. They had impressive pointers, deftly wielded, to help impart knowledge and the hardest rulers in the world to encourage discipline. They also had available on their hips extremely large sets of rosary beads coupled to enormous crucifixes. I never actually saw anyone strangled with the rosary beads or poked in the eye with a crucifix but the possibility was always there. Not that they needed weapons, really. Their steely, threatening voices were enough. Things were okay when they called you “William,” but when it got to be “Mr. Killeen,” the volcano was about to erupt. To be avoided at ALL costs was being called up to the front of the room. Not doing one’s homework was grounds for disembowelment. Some kids were always worrying about someday going to hell. Our class was more concerned about pissing off Sister Louise Clara. Say what you will, but the kids who made it through St. Patrick’s were about two years ahead of public school graduates academically, the Ultimate Imprimatur for No Pain, No Gain. Let’s leave alone the question of lifetime psychological impairments. Those vets who come back from wars with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder? Sissies, compared to graduates of nun-run Catholic schools.

Saint Patrick’s Church, Lawrence, Mass.

The Monsignor

On Sundays, of course, St. Patrick called us to his church, an imposing and attractive structure, the original of which was built in 1869 to meet the spiritual needs of the first immigrants to work in the many textile mills. The parish was large enough to populate half-a-dozen masses on Sunday, including one for kids at 8:30 a.m. on the ample lower floor. If you might be thinking of not going—which you wouldn’t, of course, that being a Hell-earning Mortal Sin—the Sisters of Charity were there taking names. Each class had its own little seating section, so, as usual, the boys and girls were separated. Unlike the schoolyard, however, there were no lines of demarcation outside the church, allowing for the unabated comingling of the sexes, much to the worriment of the nuns, who could only imagine the decadent possibilities inherent in such goings-on. To my expert knowledge, however, nobody was ever discovered grousing in the goodie or even fondling in the bushes. After all, that’s what Sunday afternoons were for.

During Lent, the lot of us were required to walk directly from class to church on Friday afternoons to celebrate the mournful Stations of The Cross, a 14-step devotional that commemorates the last day on Earth of Jesus as a man. You know what happened that day. A priest, together with a team of altar boys carrying all manner and make of clanking apparatus and dispensing incense at an alarming rate, slowly tromped from one sad sculpture to another, stopping to describe the misery Jesus and his devotees suffered at the various points of call. For kids, this was only a little less painful than falling into a tar pit with no way out. Yelling wouldn’t do any good and you couldn’t swim around in the stuff, you just had to wait until the tar abated and you could stumble out of the place in one piece. We didn’t even speak to kids who merely had to give up candy for Lent.

The saintly fellow who presided over St. Patrick’s Church was named Monsignor Daly, a monsignor being sort of an exalted priest who has given exceptional service to the Catholic Church and has probably been around awhile. Monsignor Daly, who on a good day moved at the speed of a wounded snail, had definitely been around awhile, but he still administered mass and gave sermons, often about the need for increased contributions to the collection plate, a pet peeve of my father. The monsignor, a big favorite of the nuns, was as old as Methuselah, old enough to celebrate his Golden Jubilee (50 years) as a priest, which brought about great celebration in the parish. The Sisters of Charity were on pins and needles every time he got the ague, certain it would lead to consumption or chilblain or something equally vile that would transmit him directly to Heaven and spoil the many hours of arduous labor they’d put in on the Golden Jubilee hijinks. Daly was a tough old bird, though, and he made it to the stage intact, beaming from his big throne as the music played and the plaudits rolled in. Sitting there in a row near the front, I thought that might be sorta what God looked like.

Irish Eyes Are Smiling

Graduation day from St. Patrick’s School was always held in the church, it being the only parish facility large enough to handle the crowds. We didn’t wear caps and gowns back then, the girls in white dresses, the boys in blue blazers and grey pants. The graduates sat in the front rows, the families and friends behind them. My mother made a point of being early to sit as close to the front as possible. My father was no big fan of busy affairs but he was happy some relative of his was finally graduating from something.

The hallowed Monsignor Daly, now elevated nearly to sainthood in the minds of the parishioners, presided over the festivities, handing out special awards from the altar. Things moved along nicely until the important scholarship to Central Catholic High School was handed out, an award not only prestigious but a financial gamechanger to the parents of the lucky winner. Since the scholarship was based on highest grade average, it would go to either John Barry or David Kiernan, invariably the two class leaders. What neither they nor anyone else had told anybody but the nuns, however, was that they had been offered and accepted scholarships to the world-class prep school Andover, leaving the scholarship open for someone else. When Monsignor Daly read my name from the front of the church, I couldn’t figure out what happened. All I heard then was my pal Armand Carrignan in the next row back loudly whisper in his gravelly voice, “Killer got it.” Killer was me, a name earned by chance of the word having the same first four letters as Killeen, rather than by dint of my being armed and dangerous. If my name had breen spelled K-i-E-l-e-e-n, Carrignan would probably be saying “Kielbasa got it!”

I knew the routine from watching everyone else, so I emerged from my seat, bounced down to the altar, and entered the presence of Monsignor Daly, not an everyday experience. There was a different aura about the man, far different from the run-of-the-mill priest. It took me back to the first time I visited Santa Claus and didn’t know what to do. Old as he was, his eyes were very clear, penetrating; he was not like anyone I’d ever met. I can remember the moment to this day. “Congratulations on your hard work and your award,” he said, smiling. And then he handed me the parchment. I felt like I was in some altered state, but I remembered to turn around and head back. When I approached my row, I saw my father, standing on the aisle with a rare look on his face. He was smiling. I took an extra second before I turned into my row, watching him, a little surprised. Who knew? After all this time, I had accidentally given him an acceptable gift, something he apparently valued. And he had given me one, too.

Saint Patrick

As saints go, Patrick is king of the hill, top of the heap, a guy who sits in the box seats. Everybody loves him. Do they have parades for St. Basil? I don’t think so. Do they color the beer red on St. Ignatius Day? Only in Azpeitia. When it comes to saints, there’s Patrick and then there’s everybody else. Have you ever gone across the sea to Ireland and seen the sun go down on Galway Bay? Patrick has.

That being said, what do any of us really know about St. Patrick? Not much. Nobody even knows his last name. Was it O’Callahan? Was it Muldoon? It’s a mystery. All we know is that he was born in Britain of rich but humble parents near the end of the fourth century and that he died on March 17, around 460. Long time ago, right? Nobody was keeping good records. Where were Matthew, Mark, Luke and John when you really needed them?

Anyway, at age 16, Patrick was snatched up by a band of Irish raiders who were attacking his family’s estate. They dragged him back to Erin and he sat around for six years eating gruel and doing crossword puzzles in a dump called Mount Slemish, which sounds like it should be in Israel. He also worked as a shepherd, outdoors and isolated, eventually turning to his religion for solace. I mean, it was that or hard drugs, and dealers were in short supply. It was at this time that Patrick first began thinking of converting the Irish people to Christianity.

After six years in captivity, God came to Patrick in a dream—as he reportedly so often does—and told him it was time to leave Ireland. Easy for you to say, thought Patrick, who was direly short of conveyances. He wound up walking 200 miles from County Mayo to the Irish coast, then catching a ride to Britain. After spinning his wheels for awhile and going nowhere, Patrick had another dream. No kidding. This time an angel, of all things, popped up and told him to return to Ireland as a missionary. This frosted Patrick, who thought about that 200-mile walk. “But I was already THERE once,” he protested. “Why didn’t you tell me THEN?” The angel muttered something about untrained personnel in the logistics office and flew off. Patrick dutifully began religious training, a course of study which took more than 15 years, was ordained a priest and returned to Ireland. The rest is history. Patrick travelled the length and breadth of Ireland for the next 40 years, preaching the Gospel and converting everybody in sight. His disciples, of which there were legion, spread throughout Eire, preaching and building churches all over the place.

On one occasion, Patrick was confronted by the High King Laoghaire at the Celtic feast of Beltaine, a major festival celebrating the beginning of Summer and triumph over the dark powers. Traditionally, a fire would be lit by the King on the top of the Hill of Tara and his fire would then be used to light all other fires. Patrick, however, decided to light his own fire in advance of King Laoghaire, deliberately inviting attention from the pagan chiefs. The King sent Druid elders to investigate and, if possible, extinguish Patrick’s fire. They could not. The elders advised Laoghaire that he, himself, must put out the fire or it might burn forever. The King couldn’t do it, figured Patrick’s magic must be stronger than his and decided to leave him alone. The clever saint’s followers were enthralled and excited. Patrick pulled the foremost of these aside, winked and told him, “Old party trick I learned from those inextinguishable candles. They fall for it every time.”

It’s A Great Day For The Irish

The March 17 celebration of St. Patrick’s Day started back in 1631 when the Church established a Feast Day honoring the Patron Saint of Ireland. It wasn’t until the early eighteenth century, however, that many of today’s traditions kicked into high gear. The holiday, which falls during Lent, is particularly appreciated by Catholics who have decided on some form of abstinence leading up to Easter since it gives them a day off. Modern-day celebrations and themes developed during the 1700s. In 1762, the first New York City parade took place, but it wasn’t until 1798, the year of the Irish Rebellion, that the color green became officially associated with the day. Since the British wore red, the Irish chose green, coming up with the song “The Wearing of the Green” during the rebellion.

There are now large parades held in Boston, Philadelphia, New Orleans and Savannah, as well as the grandpappy parade in NYC. In Chicago, the river is dyed green, as is the White House fountain in Washington. Irishmen get out the corned beef and cabbage and dyed-in-the-wool fanatics have been known to eat a breakfast of sausage, black and white pudding, fried eggs and fried tomatoes, rendering them unfit for anything but parade-watching and drinking green beer. Oh, and reciting limericks. Irishmen just love limericks. Even these:

There was an old girl from Kilkenny

Whose usual charge was a penny.

For half of the sum,

You might fondle her bum,

The source of amusement to many.

Had enough? Okay, how about this:

There was a young couple from Florida

Whose passions grew steadily torrider;

They planned their big sin

For a room at the inn,

Couldn’t wait and debauched in the corridor.

No need to call the police. We’re leaving now.

Happy Saint Patrick’s Day….

.